The Chequered Brilliance by Jairam Ramesh : Book Review

I READ Jairam Ramesh’s The Chequered Brilliance practically non-stop, despite its intimidating length, mainly because of its lucid style, impressive logic and sound chapterisation. As I finished reading, I was reminded of Thomas Carlyle’s (1795-1881) words: “No great man lives in vain. The history of the world is but the biography of great men.” Of course, this view of history is not cent per cent right. One is reminded of Pierre Goubert’s Louis XIV and 20 Million Frenchmen that gives a polar opposite point of view. Reflection will show that both Carlyle and Goubert are partly right.

One can say with confidence that anyone seeking to find out more than what is generally known about India’s march towards independence in 1947 and how India under Jawaharlal Nehru formulated and followed a foreign policy based on a good deal of out-of-the-box thinking should read this book.

The title of the book has been chosen carefully, foreshadowing the ups and downs in the life of an exceptionally gifted human being. When V.K. Krishna Menon started speaking for India on the world stage, the world listened, and therefore, the establishment in the West started a cottage industry of demonising him.

Some in India obediently joined in. Why did the United States want to demonise him? Because he was seen as “dangerously persuasive”. That is what the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) told MI5 of the United Kingdom. The MI5 even seriously considered assassinating Krishna Menon when he was High Commissioner in London and there were hints that he might be called back to New Delhi to join the Union Cabinet. MI5 feared that his entry into the Cabinet would carry enormous risk for the West. Fortunately, the agency reconsidered the matter. This is revealed in the book Defence of the Realm (2009) by Professor Christopher Andrew of Cambridge University.

Prof Andrew was commissioned to write the history of MI5 for its centennial in 2009. He was given complete access to its archives. India’s Intelligence Bureau (I.B.) was established in 1887. Did anyone think of publishing its history in 1987?

As a people, are Indians willing and able to look at their past with a degree of scientific objectivity without falling into the temptation of misusing the past by manufacturing fake history for settling scores in the petty political debates disfiguring the present? A sensitive reader of the book under review cannot but help raise such questions.

Jairam Ramesh has dedicated this book to his wife Jayashree who passed away before it was completed. The author narrates the life story of Krishna Menon with a command over some family issues, all the more remarkable, as we do not know whether the author who was eight years old in 1962 and 20 in 1974 when Krishna Menon died, had ever met him.

The two quotations used before the text opens are the most apposite. The first quote is that of Indira Gandhi: “A volcano has been extinguished.” The second is from K.P.S. Menon, the first Foreign Secretary of free India who had a less than cordial relationship with Krishna Menon: “But, the glow of the lava which poured out so copiously and brilliantly from it… would long remain in the memories of men and annals of history.” Is it not intriguing that Indira Gandhi and K.P.S. Menon, should have both thought of a volcano in their tribute?

Jairam Ramesh has divided the text into two sections, pre-1947 and post-1947, with seven parts, in all 21 chapters, and A Final Word. We start with A First Word, less than four pages, summarising the life and work of Krishna Menon. “He finds significant mention in histories of the negotiations over nuclear disarmament, the struggle against colonial rule in Africa, the emergence of Cyprus, the campaign against apartheid in South Africa and the crisis in Congo.” There is at least one notable omission in this list. Krishna Menon played a pivotal role in the ceasefire in the 1954 Korean War, the 1954 Geneva Conference on Indochina, and the 1956 Suez Crisis, to name a few. However, the omission is not significant as the author has meticulously covered all this in this well-researched book.

The first chapter is about the Vengali family. Krishna Menon was born on May 3, 1896, in Calicut (now Kozhikode), where Vasco da Gama set foot in May 1498, eventually leading to the capture of Goa by the Portuguese. In 1961, Krishna Menon played a crucial role in putting an end to the Portuguese rule in Goa.

Strangely enough, he was fixated on astrology and asked his sister, Janaki Amma, to send him a horoscope reading before he left London in 1952 on completion of his term as High Commissioner. The horoscope said that he would be “mentally agitated”, though there is no “danger of being unbalanced mentally”. For once, astrology was right.

Chapter 2 is titled “Annie Besant’s Protege (1918-1930)”. Krishna Menon got his Bachelor of Arts degree in economics, political science and history in 1918. He joined the Theosophical Society the same year. He taught at the National University in Madras, started by Annie Besant with Rabindranath Tagore as its first chancellor. In 1924, Annie Besant sent him to England where he joined the London School of Economics (LSE), remaining there for 10 years. Frida Laski, wife of Harold Laski, quipped that “Krishna was a chronic [perpetual student] at the LSE.” He got a BSc degree with first class honors in 1927 and later an MA in Industrial Psychology in 1931 from University College, London. He returned to LSE, registered for a PhD, which he did not complete. But in 1935, Krishna Menon got an MSc degree in economics for a thesis on English Political Thought in the 17th century.

Role in freedom struggle

One of the reasons, he did not complete his PhD is that from 1934 Krishna Menon was engrossed in political campaigning in the U.K. for India’s independence. Chapters 4 to 8, in all 258 pages, give us a detailed account of his contribution to India’s struggle for independence. Krishna Menon’s contribution is not all that well known, and the author has made a singular contribution to historiography.

Krishna Menon took over as India’s High Commissioner on August 15, 1947, and held that post until July 15, 1952. We get more than a glimpse of Sardar Patel’s dislike for Krishna Menon. Nehru appointed him as High Commissioner despite Patel’s misgivings. It is not clear why Patel did not like Krishna Menon. But it appears that Patel had, without evidence, concluded that he was close to communists, if not one of them. Patel had wrongly concluded that the U.K. and the U.S. were working at the United Nations against India on the Kashmir issue because they saw India as “too close” to Russia.

Krishna Menon lived an ascetic life even as High Commissioner. He did not draw a salary for more than six months. In April 1948, he wrote to Nehru saying that the annual salary for the High Commissioner was about £ 3,000, but he wanted to take only the living wage, say between £350 and £650. The bureaucracy wanted this matter to drag on and raised the absurd argument about a “constitutional difficulty” in having an unpaid High Commissioner. In December 1950, an exasperated Krishna Menon told Nehru that he would not draw any salary.

Jeep scandal

Everyone must have heard about the so-called “jeep scandal”. But how many of us know that Krishna Menon had not benefited financially from the deal? The transaction was made in 1951. Some persons holding high office, suffering from Krishna Menon phobia, manufactured a “scandal”. On August 24, 1954, R.P. Sarathy, Director of Audit, Defence Services, sent a “most secret” 18-page note to Nehru fully exonerating Krishna Menon. The same Sarathy had signed the 1951 audit report damning Krishna Menon. In any rational polity the matter should have ended. But Krishna Menon’s foes continued with their vicious campaign for years, assisted by a compliant media.

British intelligence, with its visceral hatred for and fear of communists, convinced Prime Minister Clement Attlee that the High Commission was a den of communists and that what the British government told Krishna Menon might reach the communists. Obviously, Attlee, who had known Krishna Menon for years, should have known better. But he swallowed the MI5 capsule hook, line and sinker. (Incidentally, we may recall that Attlee played a dirty role in the partition of India as narrated by Narendra Singh Narela in his book The Untold Story of India’s Partition.) Finally, the British High Commissioner in India conveyed to Nehru that sensitive matters would be conveyed only through him and Nehru accepted. Krishna Menon protested to Nehru and, as Jairam Ramesh says, he was in the right.

On May 14, 1952, Krishna Menon wrote to Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Janaki Amma and some others of his intention to leave this world. The originals of these letters are in the archives and one might assume that they were not dispatched. All this strengthens the view that Krishna Menon was more sinned against than sinning.

Korean War

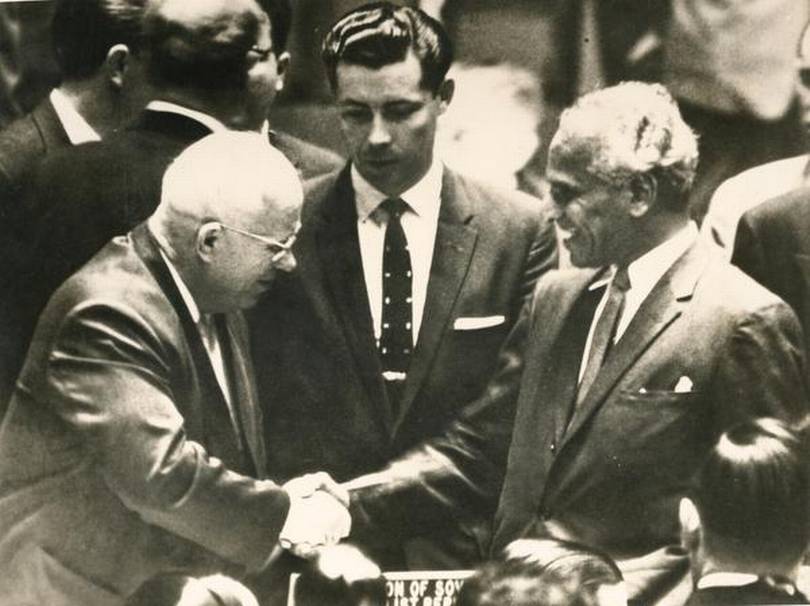

Jairam Ramesh’s account of his resolution of the prisoners of war issue in the Korean War is a study in brevity and accuracy. At one stage, Dean Acheson of the U.S., accused Krishna Menon of siding with the communists and, four days later, the Soviet Foreign Minister, Andrey Vyshinsky, called Krishna Menon “a stalking horse” for the U.S. Years later, Acheson would write of the “Menon Cabal” that included Lester B. Pearson (Canada), Selwyn Lloyd and Anthony Eden (U.K.), and R.G. Casey (Australia), “making life difficult for him”. As the author points out, Krishna Menon had divided the West.

I have found out, to my distress, that more than one political science faculty member in India is innocent of India’s role in the ending of the Korean War.

Let us look at another of Krishna Menon’s diplomatic triumphs. On April 24, 1954, Nehru read out a statement on the situation in Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) in Parliament. Nehru rarely read out from a note. Since the matter was important, he read out the note containing a six-point formula that Krishna Menon had drafted.

On April 28, 1954, 19 states met in Geneva, to discuss Korea and later Indochina. India was not among the 19. Two days after the start of the Geneva Conference, Nehru and Krishna Menon went to Colombo to attend a “mini summit” of Asian powers with Burma (Myanmar), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Indonesia and Pakistan. That summit endorsed Nehru’s six-point formula on Indochina.

The Geneva Conference on Indochina started on May 8 and for a while it was meandering. Krishna Menon reached Geneva on May 23, partly at the invitation of British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, of course with no mandate to take part in the formal sessions. He worked “behind the scenes”. Miraculously, on July 20, an agreement was announced in Geneva based on Nehru’s six-point formula.

Interviewed by the Press Trust of India in Geneva, Krishna Menon said, “I am an old fool. I am here only as a tourist; just a bystander. If people, ask to see me or come to see me, well that’s very nice.” What disarming humility from a man portrayed as arrogant, incorrigibly arrogant, by the media!

Incidentally, hardly any book on India’s foreign policy narrates in any detail this incredible diplomatic tour de force by Krishna Menon. These days, some commentators wistfully speak of India’s mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran or between Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Is there an equivalent of Krishna Menon? He had a serious shortcoming as a diplomat: He had not mastered the art of invariably suffering fools gladly. After all, there is an abundant supply of them. But seldom was Krishna Menon surpassed in the art of squaring the circle.

In 1961, Krishna Menon took the lead in liberating Goa. In a riveting account, Jairam Ramesh demolishes the myth that Krishna Menon acted without Nehru’s orders and presented him with a fait accompli. However, as regards the timing, Krishna Menon wisely told Nehru only after the action had begun. The U.S. Ambassador, John Kenneth Galbraith, was working overtime to prevent the liberation and meeting Nehru too often.

The year 1962 was crucial. The chapter is correctly titled as “The Glory and the Fall (1962)”. The author gives an exceptionally absorbing account of Krishna Menon’s landslide victory over J.B. Kripalani, president of the Indian National Congress in 1947, in the North Bombay Lok Sabha constituency in March 1962. Krishna Menon called on Kripalani at his residence after the result was declared. The reader will wonder what has happened to good manners these days among politicians.

Fighter aircraft deal

Krishna Menon was the third Indian to appear on the cover of Time magazine after Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru. Despite strident opposition from President John F. Kennedy, who roped in British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, the Air Force and the Ministry of External Affairs, Krishna Menon pressed hard and signed the MiG deal with the Soviet Union, a landmark achievement as it provided for transfer of technology and manufacturing in India. There was a good deal of correspondence between Nehru and his Defence Minister. Once again, the reader will be tempted to think of the ease with which another Prime Minister decided on the purchase of Rafale aircraft from France without the knowledge of his Defence Minister.

The author deals insightfully with the 1962 Sino-Indian war. What is striking is that all those who made a cottage industry of hating Krishna Menon found a heaven-sent opportunity to foist upon him the entire responsibility for the humiliating military debacle. Krishna Menon did make mistakes. He had discounted the threat from China. If the Indian military was caught lacking in arms and equipment, the primary responsibility is that of Finance Minister Morarji Desai who put the Defence Ministry on a tight budget.

Mao Zedong decided to strike taking into account the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. The good work done by Krishna Menon in defence production had not yet borne fruit. He established the Defence Research and Development Organisation in 1958, overcoming opposition from service chiefs. As former President R. Venkatraman, who was Defence Minister from 1982 to 1984, put it, the good work done by Krishna Menon bore fruit in the 1965 and 1971 wars.

When Lal Bahadur Shastri succeeded Nehru as Prime Minister, he wanted to send Krishna Menon as High Commissioner to London. Shastri did not want him in the capital. President S. Radhakrishnan called in the British High Commissioner to find out whether the U.K. would accept him. Prime Minister Harold Wilson was far from willing. Incidentally, the author seems to have taken care not to point out the irregularity, to put it mildly, of a head of state seeking agreement for the appointment of his ambassador.

The last four chapters of the book are devoted to Krishna Menon’s life after resignation as Minister. He tried to get back to Parliament, but the Congress refused to nominate him. He won as an independent candidate with Left support from Midnapore (Bengal) in 1969 and from Thiruvananthapuram in 1971.

Krishna Menon started his legal practice and engaged himself with Bertrand Russell and the World Peace Council. One celebrated case was that of Kerala Chief Minister E.M.S. Namboodiripad who was convicted by the Kerala High Court for saying that “Marx and Engels considered the judiciary as instruments of oppression… and even today… judges are guided and dominated by the class hatred….” Krishna Menon defended the Chief Minister in the Supreme Court, but lost the case. The court held that nowhere had Marx and Engels specifically said that about the judiciary.

The author does not forget to give us a glimpse of the women Krishna Menon was romantically close to. He lists seven.

Krishna Menon, who had advocated nuclear disarmament with religious zeal, was ill and in hospital when Indira Gandhi carried out the the peaceful nuclear explosion on May 18, 1974. He summoned her to his hospital bed and voiced his disapproval of the PNE. He passed away on October 6, 1974.

Indira Gandhi, speaking in Parliament at a meeting in honour of Krishna Menon, went down memory lane. What she said about the boundary dispute with China is significant: Had the solution which he had proposed on behalf of India in the 1950s for the India-China situation been accepted, a great deal of hardship, waste and suffering would have been avoided.

The author elaborates that in the 1950s Krishna Menon advocated a negotiated settlement on the basis of India accepting China’s claim in the West and China accepting India’s claim in the east. Nehru was “broadly supportive” but could not carry some of his senior colleagues with him.

The Jana Sangh’s Motherland saw a Voltaire in Krishna Menon, “full of wit, often pungent… The best-read politician, and with all his faults, a clean man.”

In the last chapter titled “Life after Death (1974-)” we are told about what his contemporaries thought of him, and the biographies and the academic work on him. The reader will be stunned by the Teutonic thoroughness of the author.

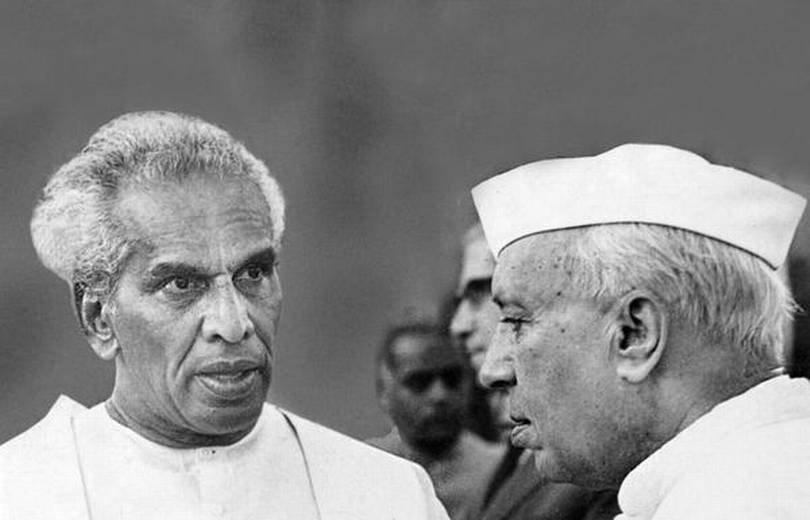

The photographs and cartoons add value to this exceptionally well-written book on a personality of abiding importance.

The book ends with “A Final Word’. “I have always believed that a good biographer should, for the most part, ascertain, not assert. Mine was not to vilify or deify” (emphasis added). The author has been true to his word.

Ambassador K.P. Fabian is Professor, Indian Society of International Law, Distinguished Fellow, Symbiosis University.

The above article written by Ambassador K.P. Fabian was initially published on Frontline Magazine

Credits:- https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/article31515845.ece