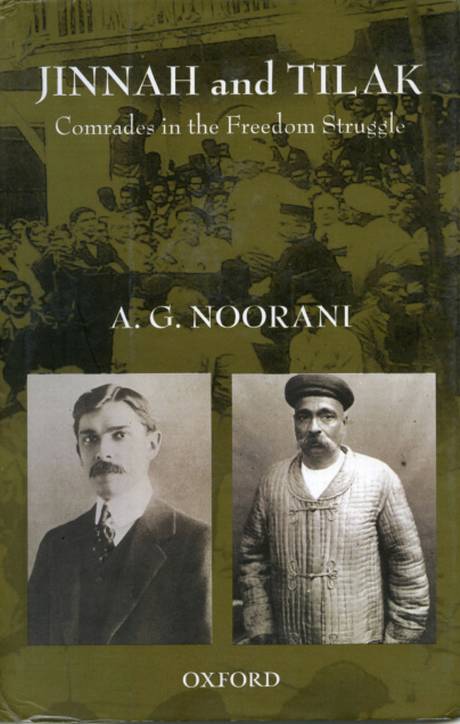

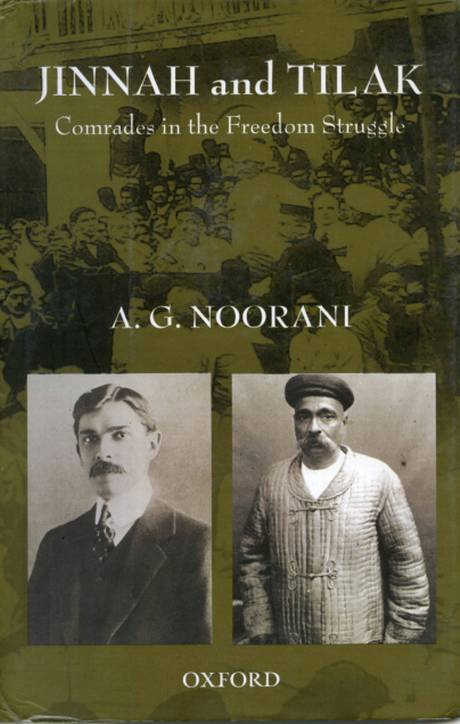

Book Review: JINNAH AND TILAK: Comrades in the Freedom Struggle

By A.G. Noorani

Oxford University Press, Karachi

Pages 465, Rs. 795

Comrades in the Freedom Struggle

The book under review by the eminent scholar- cum- advocate A. G. Noorani was published in Pakistan and it will attract much attention and debate in India. Noorani's thesis, argued with formidable skill and compelling documentary support, is that Jinnah started as a secular nationalist. The British considered him one among their most formidable opponents. Gandhi did not treat Jinnah courteously. Jinnah was opposed to Gandhi's political philosophy and importing of religion into politics. Yet, Jinnah showed remarkable tact and patience and tried hard to work with the Congress till the Hindu fundamentalists in the Congress made it impossible for him to remain there with dignity.

Even after leaving the Congress, Jinnah did his utmost to avoid partition. After the Congress declined to share power with the League in UP in 1937, Jinnah accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan in order to keep India undivided, but the Congress did not want to share power with him at the Centre. This, in a nutshell, is the true account of the partition of India in 1947. It is Gandhi and Nehru who are much more responsible for dividing India than Jinnah. He asked for Pakistan only for bargaining purposes and would have settled down for much less.

The preface starts with a quotation from Goethe: "The century gave birth to a great epoch; but the great moment found a petty generation." A definitive account of India's march towards freedom still remains to be written. For over sixty years 'court historians' have dominated academia in India and Pakistan. State control of institutions of learning, barring honorable exceptions, and misdirected patriotism account for such domination. Partition is one of the "ten greatest tragedies in the history of man."

In the first chapter aptly titled A Forgotten Comradeship the author traces Jinnah's participation in Congress starting from the 1906 Calcutta session where he opposed a resolution 'urging reservation for the backwardly educated class", meaning Moslems. The reader might note with interest that the word used is 'class' and not 'community' and that the All India Moslem League was yet to be born. Jinnah defended Tilak when he was charged with sedition in 1916 for some speeches made in Marathi. Tilak and Jinnah worked together for the reconciliation between the Moderates and the Extremists in the Congress. Jinnah who refused to join the League when it was founded in 1906, joined it only in 1913. Jinnah joined the Home Rule League and was President of the League for Bombay. He spoke at a meeting of the Home Rule League in Allahabadin October 1917, attended by over 10,000 people and his speech made it clear that he was for "mass politics." The main architects of the 1916 Lucknow Pact were Tilak and Jinnah.

When the First World War broke out and the Governor of Bombay convened a meeting of the notables, Jinnah pointed out that Indians who join the army should receive equal treatment. When the war ended and as the Governor Willingdon was leaving there was a plan to erect a war memorial in his honor. A meeting was convened in the Town Hall to gain support for the war memorial project. Jinnah took the lead in foiling the plan by flooding the Town Hall with his supporters. Jinnah and his followers were evicted from the hall by the police. But, it was a great victory for Jinnah and another meeting was held a few days later, and with each participant contributing Re.1, an amount of Rs.65,000 was collected to erect People's Jinnah Memorial Hall. The author draws attention to the fact during the 'Emergency' theBombay Committee of Lawyers for Civil Liberties was prevented from holding a meeting there.

When the 34th Congress met in Amritsar in December 1919 Tilak and Gandhi differed on the response to the Montford Report and Jinnah sided with Gandhi. In 1920, Gandhi "captured" the Congress and the Home Rule League and "bent both to his will." Jinnah resigned from Congress, but contrary to conventional wisdom "his relations with Gandhi survived the differences; survived even Gandhi's take over of the Congress." They came under strain two decades later in the late thirties. Tilak died on August 1, 1920, the day Gandhi began his non-cooperation.

The reader realizes as she goes to the second chapter After Tilak: Jinnah and Gandhi's Congress that the title of the book is slightly misleading. Tilak is brought out in the narration leading to the Partition from time to time as a counterpoint to Gandhi. The author contrasts the arrogant and autocratic Gandhi with the humble and open- to- discussion Tilak.

Jinnah, even after leaving the Congress, continued to advocate Hindu-Moslem unity against the British. In 1936, Viceroy Willingdon called Jinnah "really more Congress than the Congress." After giving a detailed account of Jinnah's political activities following his resignation from the Congress, the author concludes that "the record explodes the myths commonly trotted out to explain the radical change in the policy Jinnah adopted in the late thirties - the disagreement at the Nagpur session of the Congress in December 1920,aversion to mass politics ,marginalization, and his wife Ruttie's death on 20 February 1929. He continued to speak of Gandhi with respect long after Nagpur." The breach with Gandhi and the Congress did not occur at the Round Table Conference in London in 1930-31. "It occurred in 1937-38 when the Congress, having formed ministries in several provinces, after the first general election under the Government of India Act, 1935, refused to share power with the Muslim League. Worse still, it denied that a minority problem existed or that the Muslim League was an ally to parley on an equal footing."

In a chapter titled Wrecking India's Unity, the author explains that the Cabinet Mission (1946) came up with two plans: Plan A, a unitary India with a loose federation at the centre charged primarily with control of Defence and Foreign Affairs, and Plan B, for a divided India, with Pakistan getting exactly what it got eventually in 1947. Congress rejected Plan A, Jinnah accepted Plan A. "He was now prepared to accept Plan A which provided for a three-tier Federal Union." Though the Congress had rejected Plan A and Plan B, the Cabinet Mission went on refining Plan A. Finally, the Cabinet Mission (16 May, 1946) published its final version to be accepted or rejected, without further negotiations. The Centre will have Communications, in addition to Defence and Foreign Affairs. There will be three Groups of provinces, B consisting of Punjab, NWFP, Baluchistan, and Sind; Group C of Bengal and Assam; and Group A of the rest of the provinces. Only after the first general election could a province change its Group. Any province could reconsider the terms of its association with the Union "after an initial period of ten years and at ten yearly intervals thereafter."

The Congress saw that the Plan risked Balkanization, and took the line that the Cabinet Mission proposals were of a recommendatory nature and that once the Constituent Assembly opened it was untrammeled by those proposals. Gandhi put it clearly: "It was the best document the British Government could have produced in the circumstances. It is an appeal and advice. It has no compulsion in it." In other words, the Congress accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan with considerable reservations, openly expressed. Jinnah took the position that moved by "higher and greater considerations than any other party in India …, it had sacrificed the full sovereignty of Pakistan at the altar of Congress for securing the whole of India."

It is obvious that if the Congress and the Muslim League had engaged in good time in discussions on the modalities of Partition, it might have been possible to prevent the horrors that actually occurred. Soon after Prime Minister Atlee announced (February 20, 1947) that power would be transferred not later than June 1948, the Congress called for the partition of Punjab and Bengaland asked for consultations with the League. Despite reminders, the League refused to consult directly with the Congress and preferred to do it indirectly through Mountbatten. The author is not certain that the Congress was sincere in its offer to consult. "Its preference from 1942 onwards was to negotiate with the British." But the author does conclude that "History, assuredly, would have taken a different course if he (Jinnah) had risen to the occasion and held direct talks with Nehru and Patel since the principle of partition had been accepted in March(1947)."

The nationalist Muslims found themselves in a difficult position. Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad wrote to Gandhi towards the end of 1945 to say that the Congress needed to reassure the Muslims if it wanted their votes in the approaching election. Partition was against the interests of the Muslims. The future constitution should be federal with fully autonomous units with freedom to secede and the Centre should deal only with 'all -India subjects' and there must be parity between the Hindus and the Muslims in the Central Legislature and Central executive. This correspondence between Azad and Gandhi is not in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. V.P.Menon refers to it in Transfer of Power in India and he got it from the British intelligence who had intercepted it. Subsequently, Gandhi opposed Azad's nomination to the Cabinet and in January 1948 Patel questioned Azad's patriotism.

The chapter titled The United Bengal Episode deals with a matter not well known. In April 1947, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, premier of Bengal, proposed an independent Bengal. Jinnah confirmed to Mountbatten that he would agree to an independent Bengal. Nehru opposed an independent Bengal. Sarat Bose too wanted an independent Bengal. Bose met Gandhi along with Abul Hasim, but failed to get Gandhi's support. Mountbatten was prepared to support an independent Bengal. The author blames the Congress and Gandhi, in particular, for foiling the plans for an independent Bengal.

In the final chapter Assessing Jinnah, the author quotes Gibbon on Belisarius adding that the same verdict will apply to Jinnah: His imperfections followed from the contagion of the time; his virtues were his own, the free gift of nature or reflection. He raised himself without a master or rival and so inadequate were the arms committed to his hand, that his sole advantage was derived from the pride and presumption of his adversaries."

The author has provided texts of 27 significant documents running into 180 pages. This is indeed commendable. Jinnah's famous 14 points (1929) make it clear that he wanted a weak centre and hence a Balkanizable India.

Has the lawyer in Noorani argued his case convincingly before the readers' court? Yes and No. He has proved the case that if Gandhi, Nehru, and Patel had agreed to a weak Centre with parity between the League and the Congress at the Centre the partition in 1947 might have been avoided. But, the partition might have occurred later. The Cabinet Mission Plan contained the seed of Pakistan.

Noorani depends too much on Jinnah's public statements. We all know that politicians do not always mean what they say. In January 1946, Jinnah told Woodrow Wyatt, a Labour MP, that 'he will not take part in any Interim Government without a prior declaration accepting the principle of Pakistan, though he would not ask at that stage for any discussion or commitment on details.' Wyatt in an article (Spectator, 13 August 1997) recounts how he convinced a skeptical Jinnah that the Cabinet Mission Plan was "the first step" to Pakistan. "When I finished his face lit up. He hit the table with his hand: 'That's it. You've got it.' Obviously, they were referring to the clause that permitted Groups Band C to walk out of the Centre and form a bigger Pakistan including undivided Punjab and undivided Bengal.

The reader cannot resist raising a question: What is Noorani's idea of India? If the Cabinet Mission Plan had been adopted, there would have been a weak centre, no integration of the states effected by Patel, and India might have been Balkanized in due course. Noorani's argument is based on the assumption that there were only two choices before India: Partition and a weak Centre. He misses the point that the acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan might have led to Partition later. His plea for an independent Bengal makes it evident that Noorani wanted an easily Balkanizable India. He fails to note that there was a third choice: Partition and a strong Centre for a non-Balkanizable India. The Congress wisely chose the third option. Noorani's contention that a weak centre would have been better than partition sounds dubious.

Noorani has missed out on the role played by the Perfidious Albion. Without dwelling on the role played by Britain it is not possible to understand the genesis of partition. Let us start from the foundation of the All India Muslim League in December 1906. Viceroy Minto was behind it. His Private Secretary Dunlop Smith and Principal Archbold of the Aligarh College founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan wrote down the memorandum to be submitted by the Muslim notables to Minto. It was decided that the Agha Khan should lead the delegation. But, he was not in India and the Imperial Navy traced him to Aden and made arrangements for him to come.

Much before the 1940 March Lahore resolution calling for the division of India, Jinnah had through his deputy Khaliq-uz-Zaman consulted the British inLondon and told them that India should be divided and that the Muslim nation that will emerge will be in alliance with Britain. Lord Zetland reacted positively to the idea of dividing India. Responding to pressure from Jinnah, the Secretary of State Amery stated in the Commons on August14, 1940:

"It goes without saying that they (His Majesty's Government) could not contemplate transfer of their present responsibilities for the peace and welfare of India to any system of Government whose authority is directly denied by large and powerful elements in India's national life .Nor could they be parties to the coercion of such elements into submission to such a Government."

In plain English, as far as Britain is concerned, if Jinnah insists he shall have Pakistan. And Jinnah insisted. The Cripps Mission (1942 March), the Simla Talks (July 1945) and the Cabinet Mission (May 1946) were theatrical pieces staged by Britain, whether under Churchill or Attlee, to project to the rest of the world that it had no option but to divide India as the Indian parties were unable to come to a settlement on power-sharing in a single state despite the best efforts by the colonial power. Jinnah knew it much better than the Congress. Jinnah and Britain demonstrated a singular consistency of purpose and determination till the end. They collaborated to a degree that the third side in the triangle did not know in full. As Euclid has demonstrated two sides of a triangle together are longer than the third side. It was not that the Congress accepted partition, it was forced to concede it.

Noorani's narration of events leading to the Partition is not balanced. He omits to tell the reader that Jinnah's call for Direct Action (July 27, 1946) led to the Great Calcutta Killing starting from August 16, 1946. 5000 were killed and 20,000 were injured. Wavell's report to London exonerated Jinnah from any blame. Jinnah signaled that he would set fire to India if he did not get what he wanted.

Curiously enough, the index has an entry "Direct Action" but the reference is to the use of that phrase by Jinnah in a speech made in March 1924. Obviously, an author is not responsible for the index. Otherwise, our author would have been vulnerable to the charge of suggestion falsi et suppressio veri (suggesting what is false and suppressing the truth).

Notwithstanding the observations made, the fact remains that the author has made a major contribution to our understanding of our own history.

By A.G. Noorani

Oxford University Press, Karachi

Pages 465, Rs. 795

Comrades in the Freedom Struggle

The book under review by the eminent scholar- cum- advocate A. G. Noorani was published in Pakistan and it will attract much attention and debate in India. Noorani's thesis, argued with formidable skill and compelling documentary support, is that Jinnah started as a secular nationalist. The British considered him one among their most formidable opponents. Gandhi did not treat Jinnah courteously. Jinnah was opposed to Gandhi's political philosophy and importing of religion into politics. Yet, Jinnah showed remarkable tact and patience and tried hard to work with the Congress till the Hindu fundamentalists in the Congress made it impossible for him to remain there with dignity.

Even after leaving the Congress, Jinnah did his utmost to avoid partition. After the Congress declined to share power with the League in UP in 1937, Jinnah accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan in order to keep India undivided, but the Congress did not want to share power with him at the Centre. This, in a nutshell, is the true account of the partition of India in 1947. It is Gandhi and Nehru who are much more responsible for dividing India than Jinnah. He asked for Pakistan only for bargaining purposes and would have settled down for much less.

The preface starts with a quotation from Goethe: "The century gave birth to a great epoch; but the great moment found a petty generation." A definitive account of India's march towards freedom still remains to be written. For over sixty years 'court historians' have dominated academia in India and Pakistan. State control of institutions of learning, barring honorable exceptions, and misdirected patriotism account for such domination. Partition is one of the "ten greatest tragedies in the history of man."

In the first chapter aptly titled A Forgotten Comradeship the author traces Jinnah's participation in Congress starting from the 1906 Calcutta session where he opposed a resolution 'urging reservation for the backwardly educated class", meaning Moslems. The reader might note with interest that the word used is 'class' and not 'community' and that the All India Moslem League was yet to be born. Jinnah defended Tilak when he was charged with sedition in 1916 for some speeches made in Marathi. Tilak and Jinnah worked together for the reconciliation between the Moderates and the Extremists in the Congress. Jinnah who refused to join the League when it was founded in 1906, joined it only in 1913. Jinnah joined the Home Rule League and was President of the League for Bombay. He spoke at a meeting of the Home Rule League in Allahabadin October 1917, attended by over 10,000 people and his speech made it clear that he was for "mass politics." The main architects of the 1916 Lucknow Pact were Tilak and Jinnah.

When the First World War broke out and the Governor of Bombay convened a meeting of the notables, Jinnah pointed out that Indians who join the army should receive equal treatment. When the war ended and as the Governor Willingdon was leaving there was a plan to erect a war memorial in his honor. A meeting was convened in the Town Hall to gain support for the war memorial project. Jinnah took the lead in foiling the plan by flooding the Town Hall with his supporters. Jinnah and his followers were evicted from the hall by the police. But, it was a great victory for Jinnah and another meeting was held a few days later, and with each participant contributing Re.1, an amount of Rs.65,000 was collected to erect People's Jinnah Memorial Hall. The author draws attention to the fact during the 'Emergency' theBombay Committee of Lawyers for Civil Liberties was prevented from holding a meeting there.

When the 34th Congress met in Amritsar in December 1919 Tilak and Gandhi differed on the response to the Montford Report and Jinnah sided with Gandhi. In 1920, Gandhi "captured" the Congress and the Home Rule League and "bent both to his will." Jinnah resigned from Congress, but contrary to conventional wisdom "his relations with Gandhi survived the differences; survived even Gandhi's take over of the Congress." They came under strain two decades later in the late thirties. Tilak died on August 1, 1920, the day Gandhi began his non-cooperation.

The reader realizes as she goes to the second chapter After Tilak: Jinnah and Gandhi's Congress that the title of the book is slightly misleading. Tilak is brought out in the narration leading to the Partition from time to time as a counterpoint to Gandhi. The author contrasts the arrogant and autocratic Gandhi with the humble and open- to- discussion Tilak.

Jinnah, even after leaving the Congress, continued to advocate Hindu-Moslem unity against the British. In 1936, Viceroy Willingdon called Jinnah "really more Congress than the Congress." After giving a detailed account of Jinnah's political activities following his resignation from the Congress, the author concludes that "the record explodes the myths commonly trotted out to explain the radical change in the policy Jinnah adopted in the late thirties - the disagreement at the Nagpur session of the Congress in December 1920,aversion to mass politics ,marginalization, and his wife Ruttie's death on 20 February 1929. He continued to speak of Gandhi with respect long after Nagpur." The breach with Gandhi and the Congress did not occur at the Round Table Conference in London in 1930-31. "It occurred in 1937-38 when the Congress, having formed ministries in several provinces, after the first general election under the Government of India Act, 1935, refused to share power with the Muslim League. Worse still, it denied that a minority problem existed or that the Muslim League was an ally to parley on an equal footing."

In a chapter titled Wrecking India's Unity, the author explains that the Cabinet Mission (1946) came up with two plans: Plan A, a unitary India with a loose federation at the centre charged primarily with control of Defence and Foreign Affairs, and Plan B, for a divided India, with Pakistan getting exactly what it got eventually in 1947. Congress rejected Plan A, Jinnah accepted Plan A. "He was now prepared to accept Plan A which provided for a three-tier Federal Union." Though the Congress had rejected Plan A and Plan B, the Cabinet Mission went on refining Plan A. Finally, the Cabinet Mission (16 May, 1946) published its final version to be accepted or rejected, without further negotiations. The Centre will have Communications, in addition to Defence and Foreign Affairs. There will be three Groups of provinces, B consisting of Punjab, NWFP, Baluchistan, and Sind; Group C of Bengal and Assam; and Group A of the rest of the provinces. Only after the first general election could a province change its Group. Any province could reconsider the terms of its association with the Union "after an initial period of ten years and at ten yearly intervals thereafter."

The Congress saw that the Plan risked Balkanization, and took the line that the Cabinet Mission proposals were of a recommendatory nature and that once the Constituent Assembly opened it was untrammeled by those proposals. Gandhi put it clearly: "It was the best document the British Government could have produced in the circumstances. It is an appeal and advice. It has no compulsion in it." In other words, the Congress accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan with considerable reservations, openly expressed. Jinnah took the position that moved by "higher and greater considerations than any other party in India …, it had sacrificed the full sovereignty of Pakistan at the altar of Congress for securing the whole of India."

It is obvious that if the Congress and the Muslim League had engaged in good time in discussions on the modalities of Partition, it might have been possible to prevent the horrors that actually occurred. Soon after Prime Minister Atlee announced (February 20, 1947) that power would be transferred not later than June 1948, the Congress called for the partition of Punjab and Bengaland asked for consultations with the League. Despite reminders, the League refused to consult directly with the Congress and preferred to do it indirectly through Mountbatten. The author is not certain that the Congress was sincere in its offer to consult. "Its preference from 1942 onwards was to negotiate with the British." But the author does conclude that "History, assuredly, would have taken a different course if he (Jinnah) had risen to the occasion and held direct talks with Nehru and Patel since the principle of partition had been accepted in March(1947)."

The nationalist Muslims found themselves in a difficult position. Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad wrote to Gandhi towards the end of 1945 to say that the Congress needed to reassure the Muslims if it wanted their votes in the approaching election. Partition was against the interests of the Muslims. The future constitution should be federal with fully autonomous units with freedom to secede and the Centre should deal only with 'all -India subjects' and there must be parity between the Hindus and the Muslims in the Central Legislature and Central executive. This correspondence between Azad and Gandhi is not in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. V.P.Menon refers to it in Transfer of Power in India and he got it from the British intelligence who had intercepted it. Subsequently, Gandhi opposed Azad's nomination to the Cabinet and in January 1948 Patel questioned Azad's patriotism.

The chapter titled The United Bengal Episode deals with a matter not well known. In April 1947, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, premier of Bengal, proposed an independent Bengal. Jinnah confirmed to Mountbatten that he would agree to an independent Bengal. Nehru opposed an independent Bengal. Sarat Bose too wanted an independent Bengal. Bose met Gandhi along with Abul Hasim, but failed to get Gandhi's support. Mountbatten was prepared to support an independent Bengal. The author blames the Congress and Gandhi, in particular, for foiling the plans for an independent Bengal.

In the final chapter Assessing Jinnah, the author quotes Gibbon on Belisarius adding that the same verdict will apply to Jinnah: His imperfections followed from the contagion of the time; his virtues were his own, the free gift of nature or reflection. He raised himself without a master or rival and so inadequate were the arms committed to his hand, that his sole advantage was derived from the pride and presumption of his adversaries."

The author has provided texts of 27 significant documents running into 180 pages. This is indeed commendable. Jinnah's famous 14 points (1929) make it clear that he wanted a weak centre and hence a Balkanizable India.

Has the lawyer in Noorani argued his case convincingly before the readers' court? Yes and No. He has proved the case that if Gandhi, Nehru, and Patel had agreed to a weak Centre with parity between the League and the Congress at the Centre the partition in 1947 might have been avoided. But, the partition might have occurred later. The Cabinet Mission Plan contained the seed of Pakistan.

Noorani depends too much on Jinnah's public statements. We all know that politicians do not always mean what they say. In January 1946, Jinnah told Woodrow Wyatt, a Labour MP, that 'he will not take part in any Interim Government without a prior declaration accepting the principle of Pakistan, though he would not ask at that stage for any discussion or commitment on details.' Wyatt in an article (Spectator, 13 August 1997) recounts how he convinced a skeptical Jinnah that the Cabinet Mission Plan was "the first step" to Pakistan. "When I finished his face lit up. He hit the table with his hand: 'That's it. You've got it.' Obviously, they were referring to the clause that permitted Groups Band C to walk out of the Centre and form a bigger Pakistan including undivided Punjab and undivided Bengal.

The reader cannot resist raising a question: What is Noorani's idea of India? If the Cabinet Mission Plan had been adopted, there would have been a weak centre, no integration of the states effected by Patel, and India might have been Balkanized in due course. Noorani's argument is based on the assumption that there were only two choices before India: Partition and a weak Centre. He misses the point that the acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan might have led to Partition later. His plea for an independent Bengal makes it evident that Noorani wanted an easily Balkanizable India. He fails to note that there was a third choice: Partition and a strong Centre for a non-Balkanizable India. The Congress wisely chose the third option. Noorani's contention that a weak centre would have been better than partition sounds dubious.

Noorani has missed out on the role played by the Perfidious Albion. Without dwelling on the role played by Britain it is not possible to understand the genesis of partition. Let us start from the foundation of the All India Muslim League in December 1906. Viceroy Minto was behind it. His Private Secretary Dunlop Smith and Principal Archbold of the Aligarh College founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan wrote down the memorandum to be submitted by the Muslim notables to Minto. It was decided that the Agha Khan should lead the delegation. But, he was not in India and the Imperial Navy traced him to Aden and made arrangements for him to come.

Much before the 1940 March Lahore resolution calling for the division of India, Jinnah had through his deputy Khaliq-uz-Zaman consulted the British inLondon and told them that India should be divided and that the Muslim nation that will emerge will be in alliance with Britain. Lord Zetland reacted positively to the idea of dividing India. Responding to pressure from Jinnah, the Secretary of State Amery stated in the Commons on August14, 1940:

"It goes without saying that they (His Majesty's Government) could not contemplate transfer of their present responsibilities for the peace and welfare of India to any system of Government whose authority is directly denied by large and powerful elements in India's national life .Nor could they be parties to the coercion of such elements into submission to such a Government."

In plain English, as far as Britain is concerned, if Jinnah insists he shall have Pakistan. And Jinnah insisted. The Cripps Mission (1942 March), the Simla Talks (July 1945) and the Cabinet Mission (May 1946) were theatrical pieces staged by Britain, whether under Churchill or Attlee, to project to the rest of the world that it had no option but to divide India as the Indian parties were unable to come to a settlement on power-sharing in a single state despite the best efforts by the colonial power. Jinnah knew it much better than the Congress. Jinnah and Britain demonstrated a singular consistency of purpose and determination till the end. They collaborated to a degree that the third side in the triangle did not know in full. As Euclid has demonstrated two sides of a triangle together are longer than the third side. It was not that the Congress accepted partition, it was forced to concede it.

Noorani's narration of events leading to the Partition is not balanced. He omits to tell the reader that Jinnah's call for Direct Action (July 27, 1946) led to the Great Calcutta Killing starting from August 16, 1946. 5000 were killed and 20,000 were injured. Wavell's report to London exonerated Jinnah from any blame. Jinnah signaled that he would set fire to India if he did not get what he wanted.

Curiously enough, the index has an entry "Direct Action" but the reference is to the use of that phrase by Jinnah in a speech made in March 1924. Obviously, an author is not responsible for the index. Otherwise, our author would have been vulnerable to the charge of suggestion falsi et suppressio veri (suggesting what is false and suppressing the truth).

Notwithstanding the observations made, the fact remains that the author has made a major contribution to our understanding of our own history.

Mahan

November 8, 2011

Partition took place in 1947. Jinnah died in 1948. If Congress was not in hasty we would have avoided partition. Jinnah’s illness was well known. Man changes. Jinnah was not as adamant but seeing the opportunity became one. No doubt after taking over congress in 1920, Gandhi has bungled. Through his non-leadership he antagonized both Hindus and Muslims alike. Both Gandhi and Nehru could not stand constructive criticism. actually Gandhi represented none, Nehru represented himself and to an extent the British. Jinnah took the opportunity that came his way to represent Muslims although Muslims did not favor him. He joined Muslim league as he had no option. In other words both Nehru and Jinnah wanted their kingdoms as though claiming themselves as the princes of the country. The bad luck was a s the Kings race that took part in 1857 freedom struggle was all gone by 1947. The warrior princely race was happy with Champane and gori mems of the Britain and forgot their duty for the country.